Posts Tagged ‘DUGABO’

ache horribly

– photo by Mitch Waxman

Down Under the Greenpoint Avenue Bridge Onramp, or DUGABO as I call it, on the Queens side of the loquacious Newtown Creek, is found south of the tracks of the Long Island Railroad. A largish industrial footprint, whose boot heels were dug into the swampy soil as early at the 1830’s, both describes and damns the area. The ghosts of fat renderer and yeast brewery alike haunt the spot, as does your humble narrator.

– photo by Mitch Waxman

Wandering around down here recently, this intriguing bit of graffiti was observed. I’ve seen such markings before, over on Dutch Kills Street nearby Queens Plaza. It’s unusual mainly because of the figurative nature of the illustration, most area graffiti tends to be gang oriented, typographical in nature, or features the usage of a stylized and highly practiced logo or “tag”.

– photo by Mitch Waxman

Deeper meanings and interpretation are best left to curators and wonks, but I for one like the drawing. The text betrays the twee irony of the hipsters, in my opinion. Always remember, lords and ladies, I go to these places so you don’t have to.

“follow” me on Twitter at @newtownpentacle

central chamber

– photo by Mitch Waxman

Recently, while out on the Newtown Creek on a Newtown Creek Alliance mission, the inestimable Executive Director of the group – Kate Zidar- gestured toward a certain structure on the Queens side and asked me what I knew about it. My mandate in the organization is to act as historian, as well as photographer, and the building in question is known to modernity as the “Lukoil Getty Terminal”. It’s waterfront is categorized by Dock Code 616, a 300 foot frontage, and it sits in plain view of the Greenpoint Avenue Bridge.

To me, it will always be referred to as Tidewater.

from wikipedia

Tidewater Oil Company (also rendered as Tide Water Oil Company) was a major petroleum refining and marketing concern in the United States for more than 80 years. Tidewater was best known for its Flying A–branded products and gas stations, and for Veedol motor oil, which was known throughout the world.

Tidewater was founded in New York City in 1887. The company entered the gasoline market just before World War I, and by 1920 was selling gasoline, oil and other products on the East Coast under its Tydol brand. In 1931, Tidewater expanded its reach into the midwestern U.S. by purchasing Northwestern Oil Company of Superior, Wisconsin.

Soon thereafter, Standard Oil Company of New Jersey (now ExxonMobil) gained control of Tidewater, and set up the subsidiary Mission Corporation to operate it. J. Paul Getty’s purchase of Mission in 1937 set the stage for the birth of Tidewater as a major national player in the oil industry.

In 1938, Getty merged Tidewater with Associated Oil Company, based in San Francisco with a market area limited to the Far West. Associated, founded in 1901, had created the prominent Flying A brand for its premium-grade gasoline in 1932.

With the merger and creation of Tidewater Associated Oil Company, Flying A became the primary brand name for the company, though the Tydol and Associated names were also retained in their respective marketing areas. Tydol During the 1950s, the Associated and Tydol brands gradually fell into disuse, and were dropped entirely in 1956. That same year, “Associated” was removed from the corporate name. The Veedol trademark was retained for motor oils and lubricants. BP acquired the Veedol brand when it bought Burmah-Castrol (who then owned the Veedol brand). In February 2011 announced that they wished to sell the Veedol Brand. Tidewater operated refineries on both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, as well as a small fleet of West Coast-based tankers.

– photo by Mitch Waxman

In the early years of the American Oil industry, it seems, there were literally hundreds of small players who drilled or refined petroleum. A behemoth which emerged from the crowded field, that would dominate the sector in one way or another to this very day, was John D Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. Standard controlled the means of delivery, whether it be defacto control of the rail lines leading from oil rich regions (which were in Pennsylvania, back then) to refinery, or through ownership of the local pipelines which supplied their refined product to end use customers.

This allowed Standard to fix prices at a certain level, manipulate supply and demand in its own favor, or to keep competitors from getting their goods to market.

from 1919’s “Platts power, Volume 50“. courtesy google books

N.Y., Long Island City – The Tidewater Oil Co., 11 Broadway New York City, awarded the contract for the construction of a 2 story 30 x 140 ft warehouse on Greenpoint Ave and Newtown Creek, to H.D. Best, 949 Broadway, New York City. A steam heating system will be installed in same

– photo by Mitch Waxman

Unfair and underhanded, the Standard Trust went out of its way to destroy or stifle its competition and before long it controlled 90-95% of the oil business in the United States. Competitors came along as the years passed, most of which fell before the attentions of the Rockefellers. Some, like Charles Pratt, sold their operations to Standard and joined with it. Others were driven into bankruptcy. Technological advances and invention offered an opportunity to bypass the rail system dominated by the trust, and the dream of a pipeline which would feed oil to the independent refineries on the Atlantic coast of the United States became feasible.

The company that crystallized this challenge to Standard was the Tidewater Oil Company.

from 1889’s “Stoddart’s Encyclopaedia Americana: a dictionary of arts, sciences, and general literature“, courtesy google books

– photo by Mitch Waxman

For many years, Rockefeller and his Standard men (with their armies of bought and paid for politicians and local officials) ridiculed and fought against the pipeline company, but when his independent competitors banded together under the Tidewater brand in the 1870’s – he knew that Standard must innovate. In one of the first business moves of its kind, Standard began purchasing common stock in Tidewater, and by 1883 controlled a majority share in it.

Rather than using the well honed “breaking” techniques of industrial monopoly on the rival company, Rockefeller simply purchased his competition.

from “Harper’s magazine, Volume 72“, courtesy google books

– photo by Mitch Waxman

As an aside, it should be noted that the path Greenpoint Avenue takes, in modernity, as it crosses the Newtown Creek is slightly eastward of its ancient footprint. The modern bridge, which replaced an older swing bridge that carried LIRR and light rail tracks as well as vehicles, actually pulls traffic away from the ancestral road. In the early 20th century LUNA image linked to below, which is the inverse of my recent shot above, notice that only the bridge and rail tracks are still in place.

The Tidewater building would be to the left in the historic shot below.

X

– photo by Mitch Waxman

A recommended primer for anyone interested in the story of the early American Oil industry is “The History of the Standard Oil Company, By Ida Minerva Tarbell“, an admittedly biased and muckraking account told by the daughter of an oil pioneer whose business was wiped out by the Standard Trust. Tarbell disliked the term muckraker, and considering that she was a pioneering female journalist and investigative reporter in an age not exactly known for either- let’s just respect her wishes.

from “The History of the Standard Oil Company, Volume 2 By Ida Minerva Tarbell” courtesy google books

– photo by Mitch Waxman

Like most who opposed Rockefeller, who would die as the richest man in human history (in fact, adjusting for inflation- Rockefeller died richer than Augustus of Rome, and all the Pharoahs of Egypt, and all the kings of England- put together) Tidewater ended up a footnote, and being used as an instrument by which Standard could further dominate the competition.

Standard was broken up by the actions of the federal government in the early 20th century, shattered into several smaller corporations. Standard Oil Company of NY (SOCONY) was one of these, and it would become Mobil. Standard Oil Company of NJ (SOCONJ) would become Exxon.

Rockefeller’s bank account would one day attain sentience and become Chase Manhattan bank.

from wikipedia

In 1904, Standard controlled 91% of production and 85% of final sales. Most of its output was kerosene, of which 55% was exported around the world. After 1900 it did not try to force competitors out of business by underpricing them. The federal Commissioner of Corporations studied Standard’s operations from the period of 1904 to 1906 and concluded that “beyond question… the dominant position of the Standard Oil Company in the refining industry was due to unfair practices—to abuse of the control of pipe-lines, to railroad discriminations, and to unfair methods of competition in the sale of the refined petroleum products”.

bland face

– photo by Mitch Waxman

A lot of this Newtown Creek thing involves going to meetings in Greenpoint- this monitoring committee or that alliance or just some gathering at which an unelected official or designated regulator will speak at. This consumes quite a bit of time, which is amplified in my case, as I walk to the place from Astoria. Not a long walk by any stretch, roughly 3 miles, but sometimes it feels as if I spend all my time walking to and from the Greenpoint Avenue Bridge.

– photo by Mitch Waxman

Long have I been intrigued by this little fix a flat building which sits at the cross roads of Greenpoint Avenue, Van Dam St., and Review avenue on the Queens side in Blissville. Run down, it seems to be held together with tape and tacks, but there has always been something about the structure which has caught my eye. “Something” seems significant about it, given its location. Despite efforts at finding that something, it has always remained an enigma. Until now, thanks to the NYC Municipal Archives LUNA website.

– photo by Mitch Waxman

This shot, of the Sobol Brothers SOCONY station at the intersection of Greenpoint and Van Dam, is from August 20, 1930- roughly 82 years ago. SOCONY, of course, stands for Standard Oil Company of New York. Standard used to franchise out filling stations, in the same manner as its modern day incarnation ExxonMobil does. The name SOCONY indicates that the signage went up after 1911 when the Standard Trust was broken up, incidentally.

click here for the giant sharp version of the NYCMA image.

Also, at the ever reliable fultonhistory.com, I found this ad for the company, which seems to have had several locations in Queens.

clearing sky

– photo by Mitch Waxman

While scuttling across the Greenpoint Avenue Bridge recently, enroute to a Newtown Creek Alliance meeting featuring a presentation by the DEC’s head oil spill man -Randall Austin, this fellow was observed hard at work by one unused to such exertion. As a zoom lens was already affixed to my camera, I decided to see what might be captured, and realized that I knew almost nothing about the process of welding.

Of course, what I do know about is Newtown Creek.

from wikipedia

Welding is a fabrication or sculptural process that joins materials, usually metals or thermoplastics, by causing coalescence. This is often done by melting the workpieces and adding a filler material to form a pool of molten material (the weld pool) that cools to become a strong joint, with pressure sometimes used in conjunction with heat, or by itself, to produce the weld. This is in contrast with soldering and brazing, which involve melting a lower-melting-point material between the workpieces to form a bond between them, without melting the workpieces.

– photo by Mitch Waxman

On a basic level, I understand the process, but having never undertaken the task- am largely ignorant of its mores. Something I do know of welding, however, it that a welded tank is preferred to a riveted one for bulk storage of petroleum- which was once the industry “standard”.

Incontrovertibly, if one is at Newtown Creek, and the word “Standard” comes up- only one meaning can be gleaned.

from wikipedia

A rivet is a permanent mechanical fastener. Before being installed a rivet consists of a smooth cylindrical shaft with a head on one end. The end opposite the head is called the buck-tail. On installation the rivet is placed in a punched or drilled hole, and the tail is upset, or bucked (i.e., deformed), so that it expands to about 1.5 times the original shaft diameter, holding the rivet in place. To distinguish between the two ends of the rivet, the original head is called the factory head and the deformed end is called the shop head or buck-tail.

– photo by Mitch Waxman

The facility that this torch bearing fellow was at work in is either the Lukoil or Metro depots, but I’m never certain about the property lines in the petroleum district- and given the generally paranoid atmosphere loosed roughly upon society and caused by the ongoing Terror Wars- it’s probably best not to speculate too long about the subject of whose fence begins or ends and where the property lines are.

What’s more interesting about this spot along Newtown Creek, to me at least, is that this laborer was at work in a very special spot- historically speaking.

from wikipedia

Oil depots are usually situated close to oil refineries or in locations where marine tankers containing products can discharge their cargo. Some depots are attached to pipelines from which they draw their supplies and depots can also be fed by rail, by barge and by road tanker (sometimes known as “bridging”).

Most oil depots have road tankers operating from their grounds and these vehicles transport products to petrol stations or other users.

An oil depot is a comparatively unsophisticated facility in that (in most cases) there is no processing or other transformation on site. The products which reach the depot (from a refinery) are in their final form suitable for delivery to customers. In some cases additives may be injected into products in tanks, but there is usually no manufacturing plant on site. Modern depots comprise the same types of tankage, pipelines and gantries as those in the past and although there is a greater degree of automation on site, there have been few significant changes in depot operational activities over time.

– photo by Mitch Waxman

This was right across the street from an early (1840) Kerosene refinery- Sone and Fleming, which was later acquired by John D Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Trust and transformed into an oil refinery. This facility has been mentioned before, in connection with an armageddon like blaze which Greenpoint suffered through in 1919. Such disasters were fairly common occurrences in the early days of oil refining and storage depots, and often were caused or made worse by weaknesses in petroleum tanks that were defectively riveted.

Today, there are no refineries along the Creek, it’s all about distribution and temporary storage.

from nytimes.com

TWENTY ACRES OF OIL TANKS ABLAZE; BIG FACTORIES BURN; Flames Cross Newtown Creek from Standard Yards Storing 110,000,000 Gallons of Oil. LOSS RUNS TO MILLIONS Each Fresh Explosion Fills the Sky, as from a Volcano, with Flame and Smoke. 1,200 FIREMEN AT THE SCENE Blaze Spreads for Blocks–Two City Fireboats Catch Fire and Two of Crew Reported Missing. TWENTY ACRES OF OIL TANKS ABLAZE Burned in 1883. Crowd All But Engulfed.

also- check this photo at cah.utexas.edu out, it’s from 1919, showing the fire’s aftermath.

– photo by Mitch Waxman

Welded joins are an order of magnitude better than riveted ones in such structures. Owing to my ignorance of this industrial art, a quick check was made with a neighbor who was formerly a member of a steam fitting trade union. He instructs that a perfect weld should look like a series of quarters overlapping each other seamlessly, and that an x-ray spectrum radiological photograph can be inspected to confirm a firm and lasting fit- something which cannot be obtained with rivets.

See, you learn something new every day- here in heart of the Newtown Pentacle- along the loquacious and utterly provocative Newtown Creek..

from 1921’s Welding engineer, Volume 6, courtesy google books

____________________________________________________________________________

Click for details on Mitch Waxman’s

Upcoming boat tours of Newtown Creek

time convulsed

– photo by Mitch Waxman

As mentioned in yesterday’s posting, I spend an atrocious amount of time studying century old publications and journals found on google books. These periodicals, both trade and municipal in nature, often discuss the origins of the Newtown Creek as it exists today. At the beginning of the 20th century, when the Creek was at its arguable worst (environmentally speaking), there was a popular sentiment that engineering could fix all of its problems.

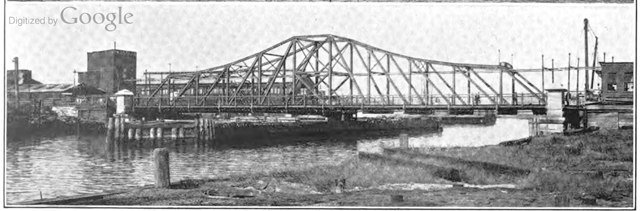

Hindsight suggests that they just made things worse, of course, but there’s the human condition for you. Pictured above is the Greenpoint Avenue Bridge in modernity, while below is the 1910 version.

– photo from Engineering magazine, Volume 38, 1910- courtesy google books

This is the bridge that burned away in the 1919 Locust Hill Oil Refinery disaster, a swing bridge not unlike the relict Grand Street Bridge found further up the Creek. Whenever such “Now and then” shots come into my hands, especially images considered to be in the public domain- they will be eagerly shared at this- your Newtown Pentacle.

For more on the history of the Greenpoint Avenue Bridge and its environs, which I call DUGABO- Down Under the Greenpoint Avenue Bridge Onramp- click here

Also:

– photo by Mitch Waxman

An NCA event, which I for one am pretty stoked about:

April NCA meeting hosts Dr. Eric Sanderson

Thursday, April 26, 2012 at 6pm

Ridgewood Democratic Club, 6070 Putnam Avenue, Ridgewood, NY 11385

In addition to important updates from our members – in particular the Bioremedition Workgroup has been very busy! – we will be hosting a special presentation on the “Historical Ecology of Newtown Creek”.

Dr. Eric Sanderson, senior conservation ecologist at the Wildlife Conservation Society and author of “Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City” (Abrams, 2009), will describe recent studies of the historical ecology of Newtown Creek, describing the original wetlands, creek channels, topography and vegetation of the area. He will show a series of 18th and 19th century maps of the watershed of the creek and discuss the process of synthesizing them into an integrated ecological picture that can be used to inform and inspire natural restoration and cultural appreciation of the Newtown Creek watershed. This work is part of the Welikia Project (welikia.org), an investigation into the historical ecology of the five boroughs of New York City and surrounding waters.

And this Saturday,

Obscura Day 2012, Thirteen Steps around Dutch Kills

Saturday April 28th, 10 a.m.

Your humble narrator will be narrating humbly at this year’s Obscura Day event on April 28th, leading a walking tour of Dutch Kills. There are a few tickets left, so grab them while you can.

“Found less than one mile from the East River, Dutch Kills is home to four movable (and one fixed span) bridges, including one of only two retractible bridges remaining in New York City. Dutch Kills is considered to be the central artery of industrial Long Island City and is ringed with enormous factory buildings, titan rail yards — it’s where the industrial revolution actually happened. Bring your camera, as the tour will be revealing an incredible landscape along this section of the troubled Newtown Creek Watershed.”

For tickets and full details, click here :

obscuraday.com/events/thirteen-steps-dutch-kills-newtown-creek-exploration