Archive for January 2012

unutterable and unnatural

– photo by Mitch Waxman

Haunting the bridges which carry pedestrian and vehicular traffic over the Sunnyside yards, as always, your humble narrator is both frustrated and relieved at the presence of the stout steel plating which obscures the track.

Frustrated, because it makes it quite difficult to photograph and bear witness to its wonders- Relieved because the vital infrastructure of the rail yard is protected from casual “sapping”.

I, of course, know where every gap in the fencing exists that is large enough to poke a camera lens through.

– photo by Mitch Waxman

The Yards are used not just by it’s main tenants- Amtrak and the Long Island Railroad- it also serves as temporary housing for the excess capacity of other area rail lines, such as the New Jersey Transit cars on the left hand side of the shot above. The ones on the right are Amtrak.

In the distance is that assemblage of early 20th century industrial splendor known as the Degnon Terminal.

– photo by Mitch Waxman

The amazing layer cake of Western Queens is manifest in this place, where the drained swamp which became the Sunnyside Yards reveals the natural grade of the land. The tracks of the 7 Subway line hang over a viaduct which exits Queens Plaza and becomes Queens Blvd.

In the distance are the former Ever Ready Battery, American Chicle, and Sunshine Biscuits “Thousand Windows” factories which were the crown jewels of the Degnon Terminal.

pest gulfs

– photo by Mitch Waxman

Not too long ago, I was crossing an intersection in Long Island City, one which is overtly familiar, and I noticed something which has eluded my interests in the past. At Hunters Point Avenue (which is officially 47th avenue in this decadent age) and 27th street, the sewers bear an interesting screed.

– photo by Mitch Waxman

There was recently a sizable road repair in this spot, perhaps in 2008 or 09, one which cut away the street surface. Observation revealed that the waters of Dutch Kills flow beneath a sort of concrete deck, which appears to be the foundations of the surface street, a structure which sits upon wooden piles.

It must have been around the time of this project that these grates showed up.

– photo by Mitch Waxman

“Dump no waste, drains to waterways” is the motto embossed on the curb surface. What this means, to me at least, is that snowmelt and rain goes directly (and untreated) into the nearest open water- which would be the Dutch Kills tributary of the fabled Newtown Creek.

Just in case you think that this is not a big deal, this is an enormously well travelled intersection with a UPS depot on the opposite corner and one which provides a “short cut” for trucks employed by the Fresh Direct facility on Borden Avenue (amongst others, of course). That’s two very large fleets of trucks.

Trucks are notoriously “drippy” and their exhaust paints the pavement with diesel petroleum residue, all of which flows into the water.

– photo by Mitch Waxman

Another drop in the bucket, you might say, as far the Newtown Creek Watershed goes.

Even so, it’s odd that untreated wastewater is allowed to flow directly into this waterway, already a largely anaerobic place where no fish of similar size might survive long.

gangrenous glare

– photo by Mitch Waxman

Just a short one today, as your humble narrator has recently been laid low by some unknown virus for the last week, and frankly- all I can manage in this state of epidemic weakness and fatigue is another of the “now and then” posts.

Doubt exists in my mind as to the exact location of the shot below, but there were several improvements made to the elevated line on Queens Blvd. over the years, some of which were due to the lengthening of the platforms to accommodate IND as well as IRT to facilitate system wide access to the World’s Fair at what is now Flushing Meadow Corona Park.

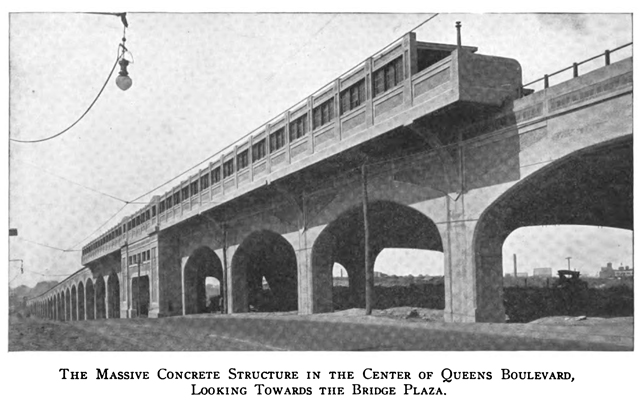

– photo courtesy google books, from: Queens Borough, New York City, 1910-1920: The Borough of Homes and Industry

This very well might be the 46th street station in Sunnyside… but I’ll also point out that the Chrysler Building is missing as well.

many candles

– photo by Mitch Waxman

Another one of NY Harbor’s towing companies whose craft are a delight to behold is DonJon Marine.

They operate a fleet of sky blue tugs whose capabilities range from canal and river tugs all the way up to a gargantuan oceanic tug which is called Atlantic Salvor.

Today, the focus is on DonJon’s Cheyenne, which is one of their smaller tugs. That’s her, moving past Wards Island and passing beneath the Hells Gate Bridge.

from donjon.com

Founded in 1964 by Mr. J. Arnold Witte, Donjon’s President and Chief Executive Officer, Donjon Marine’s principal business activities were marine salvage, marine transportation, and related services. Today Donjon Marine is a true provider of multifaceted marine services. Donjon’s controlled expansion into related businesses such as dredging, ferrous and non-ferrous recycling and heavy lift services are a natural progression, paralleling our record of solid technical and cost-effective performance.

– photo by Mitch Waxman

Cheyenne is older than I am, yet manages to get to work every day, unlike me.

DonJon serves as one of the integral components of New York Harbor’s system for moving recyclable commodities from curb to customer, and can often be spotted moving barges of metallic waste between DSNY collection points.

I first became aware of the company’s role in the process after spotting them at the SimsMetal Newtown Creek docks a few years ago.

Built in 1965, by Ira S. Bushey and Sons of Brooklyn, New York (hull #628) as the tug Glenwood for Red Star Towing.

In 1970, she was acquired by Spentonbush Towing where she was renamed as the Cheyenne

The tug was later acquired by Amerada Hess where she retained her name.

She was then acquired by Empire Harbor Marine where the tug retained her name. The company would later be renamed as Port Albany Ventures.

In 2009, Port Albany Ventures was acquired by the DonJon Marine Company of Hillside, New Jersey.

– photo by Mitch Waxman

A dirty and necessary industry, recycling is nothing like you would imagine it to be. University professors, environmentalists, and politicians present an image of something akin to Santa’s Elves in crisp white uniforms working in an antiseptic factory isolated from population centers. The reality is that it is performed by oil streaked and smoke belching heavy machinery, consumes far more fuel than you would imagine, and that it is quite a dangerous occupation (also, the concentration and processing of these metals carries dark implications for groundwater and air quality in the localities which it takes place in).

Green jobs of the future indeed.

from wikipedia

The scrap industry contributed $65 billion in 2006 and is one of the few contributing positively to the U.S. balance of trade, exporting $15.7 billion in scrap commodities in 2006. This imbalance of trade has resulted in rising scrap prices during 2007 and 2008 within the United States. Scrap recycling also helps reduce greenhouse gas emissions and conserves energy and natural resources. For example, scrap recycling diverts 145,000,000 short tons (129,464,286 long tons; 131,541,787 t) of materials away from landfills. Recycled scrap is a raw material feedstock for 2 out of 3 pounds of steel made in the U.S., for 60% of the metals and alloys produced in the U.S., for more than 50% of the U.S. paper industry’s needs, and for 33% of U.S. aluminum. Recycled scrap helps keep air and water cleaner by removing potentially hazardous materials and keeping them out of landfills.

– photo by Mitch Waxman

Not meaning to sound negative on this otherwise essential service, it’s just that as certain highly placed municipal employees have advised me in the past- “Be careful which laws you ask for, as some things may come only at too great a cost”.

If it costs ten gallons of fuel to recycle and reuse something which it would have cost five gallons of fuel to pull out of the ground… what are we actually saving?

from wikipedia

The tugboat is one symbol of New York. Along with its more famous icons of Lady Liberty, the Empire State Building, and the Brooklyn Bridge, the sturdy little tugs, once all steam powered, working quietly in the harbor became a sight in the city.

The first hull was the paddler tug Rufus W. King of 1828.

New York Harbor at the confluence of the East River, Hudson River, and Atlantic Ocean is among the world’s largest natural harbors and was chosen in the 17th century as the site of New Amsterdam for its potential as a port. The completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 to the upper Hudson River ensured that New York would be the center of trade for the Eastern Seaboard, and as a result, the city boomed. At the port’s peak in the period of 1900-1950, ships moved millions of tons of freight, immigrants, millionaires, and GI service men serving in wars.

Sheparding the traffic around the harbor were hundreds of tugs–over 700 steam tugs worked the harbor in 1929. Firms such as McAllister, and Moran Tugs came into the business. Cornelius Vanderbilt started his empire with a sailboat and went on to greatness with the New York Central Railroad, incidentally owning many tugs.